Wings of Desire

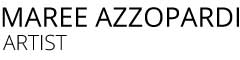

Spirit # 1- 4 series, each is digital print on line, 50x70cm 2019

Slumber

Hush – Memento mori series

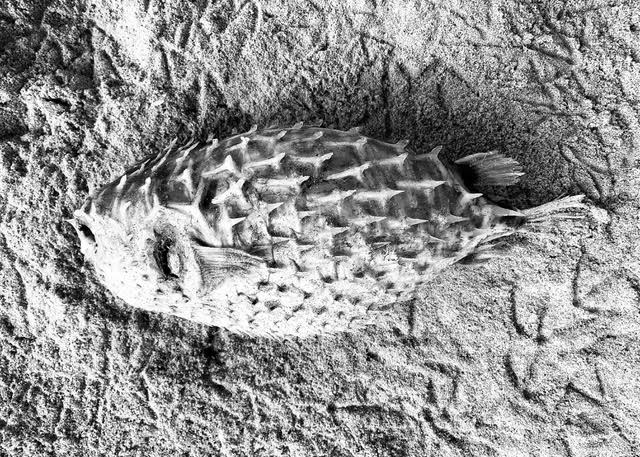

Ichthys Series all are 50 x 70cm digital print on linen

Maree Azzopardi’s new works continue the artist’s ongoing engagement with themes of the human body, religious symbolism, and the polarities of earth and water. Her photographs act as memorials for the people or places they remember and record. They include personal memories and family narrative and the works explore themes of loss, retrieval, commemoration and bearing witness. For the first time, the artist has printed photographs onto linen. These works harness the symbolic power of linen in Catholic ritual and iconography, especially altar cloths and the practice of shrouding the dead. Curator Christine Morrow Touseant

Maree Azzopardi Exquisite Corpse: I loved you more

Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau

The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine

Full of poetry and paradox, this short sentence is thought to be the first one generated by a kind of game the French Surrealists played in Montparnasse, Paris, in the second or third decade of the 20th Century[1]. It has come to be known as cadavre exquis or exquisite corpse.

The rules of the game were that players would contribute a noun, an adjective, a verb, and so on in turn. No one knew what word or words preceded their own. The idea was that a curious sentence would emerge, full of random and startling conjunctions.

Or would it?

This purportedly illogical sentence—The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine—

is highly sensical, powerful and revelatory. The adjective ‘exquisite’ tells us it’s a tale of extreme beauty. The word ‘corpse’ gives us flesh, death and decay. In the corpse’s post-death capacity for consumption—the drinking of the new wine—we can uncover the promise of an afterlife. Each new vintage is a seasonal rebirth following a pattern of fruiting, ripening, harvesting, and fermentation. The drinking of wine alongside a story of death, regeneration and resurrection even hints at the twin motifs of transubstantiation and the sharing of a sacrificial meal that together make up the ritual of the Catholic Mass.

These remarks address the symbolic referents of the individual words. But what of the sentence’s form and structure? It reads as a kind of decree or prophecy. For the extravagance of its imagery, as well as its biblical overtones, it might nearly be from the Book of Revelation. It could find as fitting a home in the Christian liturgy as among the artistic avant-garde.

This is the paradoxical space Maltese-Australian artist Maree Azzopardi carves out for herself: artistic expression based on poetic and potent symbolic conjunctions, and a visual language informed by Roman Catholic representations of death, sacrifice, ritual and afterlife.

In this new exhibition, whose title—Exquisite Corpse: I loved you more—borrows from the surrealist game, Azzopardi returns to those subjects of death, human flesh, decay, mourning and commemoration that have informed her practice off and on at different stages of her career. While Maree Azzopardi is packing her works for the flight from Sydney to Valletta, the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris is burning, Christians are preparing for the holiest day in their calendar, Good Friday, and two military allies that bookend the artist’s cultural identity, Malta and Australia, are planning the ANZAC day ceremonies that commemorate the sacrifices of the war dead. Azzopardi’s motifs reverberate alongside.

For the first time, the artist has printed photographs onto linen. Her works draw from the symbolic power of cloth in Catholic ritual and iconography—the altar cloths, among them, the corporal; the swaddling clothes at Christ’s birth; the Veil of Veronica; Christ’s garments distributed among the soldiers at the Passion according to the casting of lots; and the empty winding sheet seen by Peter and John on the day of the resurrection. Cloth wicks away wine, water and blood. And resonates symbolically too. In Bernini’s famous sculpture Saint Teresa in Ecstasy in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, folds of linen ripple the marble making cloth a means for the compression and expression of emotion.

Azzopardi’s photographs are sombre and austere in their monochrome tonality; black and white images printed at a domestic scale. The death themes; the intimacy of the subject matter; the tight confines of the pictorial framing; and the way the images revel in their fragments and details: these all transport us to the world of Victorian mourning.

In the past, Azzopardi’s images have sometimes depicted the vast, amorphous spaces of sky and sea and invoked themes of eternity and the sublime. This time she returns to claustrophobic vignettes of intimate subjects around themes of longing and loss. No living figure is more vulnerable than a sleeping body, naked and recumbent; no dead figure is more affecting than a body laid out optimistically in its grave clothes; no space is more private than the coffin or the bed.

The exhibition encompasses five distinct but interrelated series: Wings of Desire, Memento Mori, Slumber, Spirit and Ichthys. They are linked by the ways they mediate between the flesh and spirit. Wings of Desire, Memento Mori and Ichthys depict dead bodies and bear witness to the extinction of life. But they do not have a documentary function. Their purpose is not to provide a matter-of-fact recording of passing material reality. They require that we pause and acknowledge the human and animal subjects they remember and record. Yet they don’t see death as final. Instead, these images have the same symbolic function as funerary rites: to decouple the dead body’s soul so that the flesh may safely return to earth while the spirit is unfurled. Azzopardi’s artistic strategy is to produce visible artefacts embedded in the material world—images on printed cloth—to evoke the invisible and anti-material: a life-spirit that is unspoken and unseen.

The series Ichthys takes its name from a simple iconographic sign made of two opposing curves intersecting twice to produce a stylised fish shape. It operated as a secret symbol for Christianity from the early days of the church. In Azzopardi’s works, the dead fishes on the beach breach the liminal zone between earth and sea. The reveal death as a brief, transgressional interpenetration of two realms.

The series Spirit references the figure of the shaman. Featuring a living man portrayed alongside a dead animal talisman, they remind us that the role of the shaman is to mediate between the living and the dead, to open and operate channels of energy between the physical and spirit worlds.

Wings of Desire (Der Himmel über Berlin) takes its name from a 1987 Wim Wenders film that proposes a different kind of mediation between the immaterial and material realm. The main plot theme is that an angel (invisible and immortal) becomes human (visible and mortal). The film uses black and white sequences to represent the angels’ point of view and colour sequences to depict the earthly, material realm. The film’s main premise is the exploration of the transitions, parallels and ruptures between the two.

Not unlike the fishes of Ichthys, Azzopardi’s photographs in Wings of Desire portray dead birds on the sand. While alive, birds span the two realms of material earth and nebulous sky. They act as conduits between. In the parent tongue of all the Indo-European languages, the word for humans is earth-beings and the word for gods is sky-beings. The earth is the realm of the flesh and the sky is the realm of the spirit. These dead bird bodies are sky-borne beings repatriated to the earth. Spirit collapsed back on its flesh. Death into dust.

The images of Slumber mourn the end of a relationship. They portray the body of a woman, calm and contained, hushed and enigmatic. Slumber may be a metaphor for death but the turbulent ridges in the bed clothes reassure us these are restless scenes of the living.

In Wings of Desire and in Memento Mori, tiny sections are picked out in embroidered gold thread. They impart preciousness, the same way that gilding frescoes gives them a shimmering radiance. The gold accents on the photographs may be seen as examples of the ‘punctums’ introduced by Roland Barthes in his book Camera Lucida (1980). This word refers to the poignant detail that emotionally connects the viewer to the photograph’s subject. Barthes’ anthology of short texts intimately links photography with death. His writing is riddled with sentiment. Barthes explains that the emergence of this strange book followed his mother’s death, when he found himself searching for glimpses of her in old photographs. However, photos may not satisfy our desire to retrieve and reclaim the ones we have loved. In photographs, people may instead be relegated forever to the realm of the lost. Perhaps the gold threads that pierce these images of Azzopardi’s betray her attempt to anchor what is slipping away.

The exhibition Exquisite Corpse is entirely a work of mourning. It follows the death of the artist’s father. If you are a writer, like me, in a culture that is literary, you may opt to perform your grief through a written or spoken eulogy. If your culture expresses itself through ritual like in Aboriginal Australia, and like in the Catholic rites of the churches in Malta, Australia or elsewhere, you will wail the dead and deliver the release of the spirit to its resting place through dance or ceremony. But an artist like Maree Azzopardi speaks out her loss through the image, through the stitching and via the cloth.

Among the works are some that depict Maree Azzopardi’s father in his grave clothes. After his death and burial in Australia, the artist’s journey with these works retraces in reverse the emigrant voyage her father once took. Among the Maltese diaspora is a heart-sickness of living between two worlds. It affects foreign-born children even more than their migrant parents. Between two places, there is nothing but turbulence. But in the shamanistic promise that two realms may be bridged, Azzopardi finds a release.

The artist-as-shaman, Maree Azzopardi, has formed a conduit between two worlds. Her father’s flesh is buried in Australian soil. But with these images and this exhibition, she is repatriating his spirit to the land of his birth. Maree Azzopardi is bringing her dead father home.

Christine Morrow

Brisbane, Australia, April 2019

[1] It origins are the subject of dispute; variously attributed to either 1918 or 1925.